Local Solutions with Global Reach - Can Civic Tech Benefit from Open Source Software Ecosystem Practises?

21 Oct 2020 · 9 min readPreamble

Recently my colleagues and I had the opportunity to participate in the Civic Technologies workshop arranged online at the Computer-Supported Cooperative Work 2020 conference. Since it is allowed with workshop papers, we are re-publishing our text below as an online article. Read more below, if you’d like to find out more about how civic tech could be viewed through the lens of open source software ecosystems.

In this article, we identify benefits of using open source ecosystem practices within civic tech projects, the barriers against it, and offer some technical solutions that could address some of these barriers. We also lay the foundation for looking into less tangible aspects such as mutual benefits between the communities and cross community learning.

Authors and publication

Knutas, A., Palacin, V., Wolff, A., & Hyrynsalmi, S. (2020). Local Solutions with Global Reach - Can Civic Tech Benefit from Open Source Software Ecosystem Practises? In CSCW 2020 Workshop on Civic Technologies: Research, Practice, and Open Challenges. ACM. (Preprint from LUTPub)

Read on for the full paper below.

Local Solutions with Global Reach — Can Civic Tech Benefit from Open Source Software Ecosystem Practises?

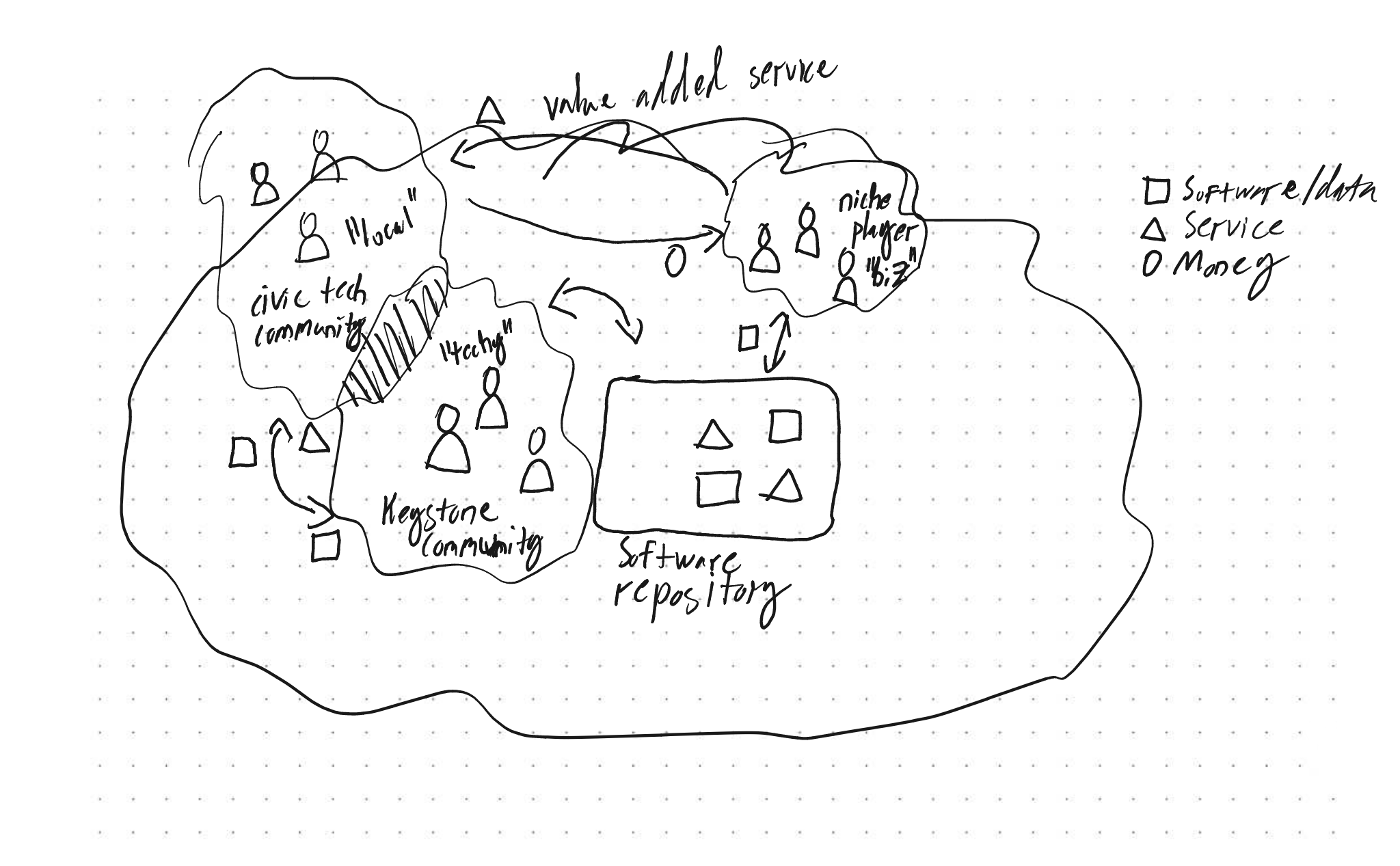

Figure: One possible view into civic tech ecosystems, following notation by 1

Figure: One possible view into civic tech ecosystems, following notation by 1

Introduction

Civic technology refers to the diverse ways in which people are using technology to influence change in society (Boehner and DiSalvo 20162; Knight Foundation 20133; Steinberg 20144). There are a variety of creators of civic tech, ranging from commercial actors, governments, non-profits, volunteer organizations, and loosely organized communities (Sifry, Stempeck, and Simpson 20175). These creators vary in purpose (Saldivar et al. 20196) and in how they identify themselves as practitioners (Costanza-Chock et al. 20187).8 What is common in all of these projects, is that they address a societal need identified by the public, or together with the public. For example, the need to identify air pollution, increased transparency, or participatory governance.

Civic tech projects are often partly or fully driven by volunteers, they might lack involved technologists, and the people invested in solving social issues are not always well resourced. Due to this, it is important that software supporting civic technology would be easily available and shared by successful civic tech projects. This can be a challenge due to the fact that civic tech solutions are created together with or bespoke for the community, on the other hand empowering that specific community, but at the same time making them more difficult to share and customize. Furthermore, making software more adaptable requires more effort and resources, and that is rarely the main goal.

Several civic tech groups already consider Free/Libre and open source software important, seeing its values to be consistent with the goals of equity, justice, transparency, and sharing instead of competition (Costanza-Chock et al. 20187; Smith and Martı́n 20209). Despite this, poorly resourced projects might turn to commercial or closed software, which is easy to take into use, but at the same time lacks community accountability and transparency, and might ultimately work at cross-purposes with the positive social change the community seeks.

Currently civic tech groups share certain types of resources and knowledge, such as best practises and processes for better co-design or equability. We propose that examining civic technology projects through the lens of open source software ecosystems, could bring additional value in the form of thinking of new ways and processes to efficiently share software solutions, without losing the values that are central to civic tech.

In this position paper, we first briefly review the concept of open source software ecosystems, present different artefacts and methods that those ecosystems share, and then discuss how those methods could be harnessed by civic tech projects in future research.

Open Source Software Ecosystems

Open source software emerges from a loosely coordinated, unsupervised community of volunteering developers and other contributors to address a specific need (Franco-Bedoya et al. 201710). If an open source software community grows, an ecosystem may grow around it.

Open source software ecosystems (OSSECO) have two fundamental factors: network of organizations or actors and a common interest in a central software technology (Messerschmitt, Szyperski, and others 200511) or a shared market for software and services (Jansen, Cusumano, and Brinkkemper 201312). OSSECO in turn can be defined as a “a software ecosystem placed in a heterogenous environment, whose boundary is a set of niche players and whose keystone player is an open source software community around a set of projects in an open-common platform” (Franco-Bedoya et al. 2017, 2410). A review by Franco et al. (Franco-Bedoya et al. 201710) lists several characteristics unique to OSSECO, which include software distribution paradigms including source code and repositories, license schema facilitating the relationship of keystone players (OSS community) and niche players (partners, providers, adopters), and the OSS community dominating the development rather than an individual organization. Example OSSECOs include for instance the Debian Linux operating system13, or the Jitsi Meet call platform14.

What is similar in OSSECOs and civic tech groups is that both have a community as the key player. What is dissimilar is that OSSECOs centre the software and are formed of a decentralised network that form an online community, whereas civic tech centres the problem (rather than the solution mechanism, which may or may not entirely be tech related) and the community is at least more likely to be primarily physical.

Some examples already exist at the intersection of OESSECO and civic tech. For example, it could be argued that for example Luftdaten15 is both civic tech movement for cleaner air and an open source software ecosystem around a citizen sensing platform developing open source software for both the platform and diverse measurement devices. Luftdaten also provides other open resources, such as an open data platform.

Discussing Opportunities at the Intersection of Civic Tech and Open Source Software Ecosystems

In this section, we present four discussion points on OSSECO practises and relate them to civic tech.

-

Generalizing and sharing common components or services. Current software engineering practises allow modular architecture and sharing software components through technologies such as micro-architecture design and containerization. This would allow sharing underlying software components without compromising co-designed functionality.

-

Providing community-controlled deployment options through niche players. In OSSECOs, niche players can enhance resources by providing a better user experience. For example, various Linux distributions provide a graphical way to install open source software from repositories. The Alphabet company provides an automated way to install open and secure networking software to a server of user’s choosing. Better deployment and configuration features would reduce the need for technical expertise, while allowing the community to retain control.

-

Supporting capacity building and resilient solutions. Currently most resources and attention to go new tools, despite there being a need for resilient solutions (Costanza-Chock et al. 20187). If communities centering on maintenance, upgrades and support were supported better, it would help making more sustainable solutions.

-

Managing and cultivating the ecosystem. Many successful civic tech projects acknowledge the community as a central actor and center its needs. Similarly, volunteers and community actors in software development require support. In software ecosystems, OSSECOs try to monitor the ecosystem health and support the ecosystems through diverse methods.

Lastly, we differentiate between the technical aspects that facilitate sharing, such as the use of open source practises within civic tech communities, and other less tangible methods of sharing. These other aspects, such as how open source projects could learn from civic tech’s equitable design practises or addressing technology biases, are important but out of scope in this particular paper. We propose that these topics should be addressed in future research.

References

-

Juergen Musil, Angelika Musil, and Stefan Biffl. 2013. Elements of software ecosystem early-stage design for collective intelligence systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Workshop on Ecosystem Architectures (WEA 2013). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 21–25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/2501585.2501590 ↩

-

Boehner, Kirsten, and Carl DiSalvo. 2016. “Data, Design and Civics: An Exploratory Study of Civic Tech.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2970–81. ACM. ↩

-

Knight Foundation. 2013. “The Emergence of Civic Tech : Investments in a Growing Field” http://www.knightfoundation.org/media/uploads/publication_pdfs/knight-civic-tech.pdf. ↩

-

Steinberg, Tom. 2014. “‘Civic Tech’ Has Won the Name-Game. But What Does It Mean?” https://www.mysociety.org/2014/09/08/civic-tech-has-won-the-name-game-but-what-does-it-mean/. ↩

-

Sifry, Micah, Matt Stempeck, and Erin Simpson. 2017. “Civic Tech Field Guide.” https://Civictech.guide* ↩

-

Saldivar, Jorge, Cristhian Parra, Marcelo Alcaraz, Rebeca Arteta, and Luca Cernuzzi. 2019. “Civic Technology for Social Innovation.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 28 (1-2): 169–207. ↩

-

Costanza-Chock, Sasha, Taya Wagoner, Berhan Taye, Caroline Rivas, Chris Schweidler, Georgia Bullen, and the T4SJ Project. 2018. “#MoreThanCode: Practitioners Reimagine the Landscape of Technology for Justice and Equity.” Research Action Design & Open Technology Institute. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Terms that the groups identify as include free software, digital literacy, community technology, and inclusive design. ↩

-

Smith, Adrian, and Pedro Prieto Martı́n. 2020. “Going Beyond the Smart City? Implementing Technopolitical Platforms for Urban Democracy in Madrid and Barcelona.” Journal of Urban Technology, 1–20. ↩

-

Franco-Bedoya, Oscar, David Ameller, Dolors Costal, and Xavier Franch. 2017. “Open Source Software Ecosystems: A Systematic Mapping.” Information and Software Technology 91: 160–85. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Messerschmitt, David G, Clemens Szyperski, and others. 2005. “Software Ecosystem: Understanding an Indispensable Technology and Industry.” MIT Press Books 1. ↩

-

Jansen, Slinger, Michael A Cusumano, and Sjaak Brinkkemper. 2013. Software Ecosystems: Analyzing and Managing Business Networks in the Software Industry. Edward Elgar Publishing. ↩

-

https://www.debian.org ↩

-

https://jitsi.org/jitsi-meet ↩

-

https://luftdaten.info/ ↩